What should one do if a tornado is approaching your location?

A few years ago there would be no such discussion. Tornado warnings were either non-existent or provided with insufficient lead time for doing anything other than finding the safest location close at hand. As recently as 1987, the average tornado warning time for the National Weather Service was around 4 minutes, while today it is about 15 minutes. Moore, OK was warned about 35 minutes before the tornado hit the city.

The trend towards increasing lead times should continue for a number of reasons:

- The NWS is still learning how to use its recently upgraded (to dual-polarization) Doppler weather radars, radars that can now sense debris lofted by tornadoes.

- Next-generation radars currently being tested (phase-array radars) will produce updated images every minute rather than the 5-6 minutes of the current NWS radars.

- Improved modeling technology, and particularly high-resolution rapid-refresh forecast systems using ensemble-based data assimilation, should substantially improved forecasts up to 3 hr out.

- New observing technologies, including pressure measurements from smart phones, better satellite information, and instrumented commuter planes will be of substantial benefit. In a few years, most cars will have internet and will be able to provide pressure and other weather information.

- Far better delivery systems. Smartphones are extraordinary good weather warning delivery systems. They even know where you are!

- Extraordinary assets being put together by local TV stations, including chase helicopters and spotters providing live feeds.

- Improved understanding of severe convection. My colleagues at University of Oklahoma, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, the Storm Prediction Center, the National Severe Storms Lab, and other research entities are making important strides.

But significant number of people are still getting killed and injured...what are we going to do about it?

The traditional recommendation given to the public is to find shelter. Find a tornado shelter if possible, and if not to go to the lowest floor of a building, preferably an interior room. In most cases, this is still good advice.

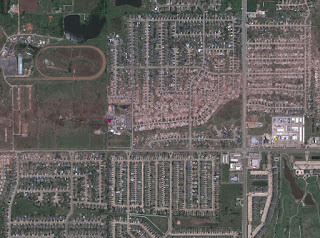

But many folks don't have access to a tornado shelter, a below-ground tornado cellar, or a specially engineered safe room in their home. Greater warning time makes it very tempting to flee, and quite frankly many in Moore, OK did just that--which perhaps explains why only about a half-dozen folks were killed when thousands of buildings were damaged or destroyed. But Moore had a huge warning time, is a relatively low-density community, and the tornado did not hit at rush hour. Looking at the damage to Moore (and most tornadoes) you can see why fleeing is so attractive: the damage path is really quite narrow (1/2 -1 mile is wide for tornadoes). You could WALK out of the damage path with 15 minute warning IF it were known.

Furthermore, the tracks of most tornadoes are relatively straight (see image), so there are not a lot of surprises. But, of course, there are exceptions to such relatively straight paths--like the El Reno tornado in OK City on Friday that took an unexpected turn, resulting in the deaths and injuries of some experienced storm chasers.

The Oklahoma City tornadoes on Friday showed what happens when folks try fleeing in a more populated region: the roads go into grid lock and people are trapped in their cars--like sitting ducks. Nearly all the people who got killed in Oklahoma City were in vehicles. Most clearly would have survived if they had sheltered somewhere.

So what is the answer: flee or shelter? My take (and I am not an official voice for anyone) is that we need a little bit of both.

For folks in rural locations where traffic will not be a problem, flight from danger can make a lot of sense, particularly if one does not have a tornado-safe shelter.. And they should have two flight options: (1) move to a location of greatly reduced tornado risk (which we can't be 100% sure of) based on the latest forecast/radar guidance or (2) go to a nearby public tornado shelter. Clearly, Oklahoma and neighboring states need to make the public investment in large safe locations...every public school should have one, for example. And, one needs to bite the bullet and require all new construction to have a safe room or cellar. We require special roof tie-downs in hurricane zones, so this is not a new concept.

To aid decision making, the NWS should develop a special tornado app for smartphones. It would know your location and direct you to the nearest shelter (perhaps even within walking distance) or tell you which way you should drive if you wished to take that option. The app would have traffic information (via a feed from the google maps capability perhaps) that would be used to tell you the best routing to your choice. And it would tell you whether you would be hopelessly trapped in traffic. If this app was really sophisticated, it would route people to minimize overcrowding of shelters and traffic. And with knowledge of real-time rainfall, it could even keep folks away from low-lying areas that might flood. There are already a number of smartphone apps dealing with severe weather...we need the next generation approach that provide guidance on how to find safety.

In urban areas, the potential for grid lock increases rapidly and taking shelter should be the main approach. Again, we need to insure there are a large numbers of safe locations. Some will need to be built, but urban areas have more strong structures (steel frame, reinforced concrete buildings, parking garages) that are better able to take EF-4 or 5 winds.

In short, with improved tornado forecasts, an investment in shelter infrastructure, development of appropriate smartphone apps, and a more organized and rational approach to the tornado threat, I suspect we could reduce tornado injury and deaths by a huge proportion. But it will take a will do to do so and some public investment.

No comments:

Post a Comment